Social licences have become the premise of Justin Trudeau’s thought-provoking policy about energy-project developments. They have also be a main reason why western provinces and the business community have started to doubt the best minister’s leadership and the willingness to stand for a healthy energy sector.

To begin with, nobody exactly understands (and never will) exactly what a social licence is. Yet, a minimum of a couple of things know.

First, the extractive business industries deeply transform ecological milieus, communities and economies – and often generate conflicts.

Second, getting a social licence involves a comparatively broad and unpredictable consultation process where local communities can provide an opinion, be heard, and finally, in extraordinary instances, exercise a veto.

Would relationships between local neighborhoods and also the energy sector in Canada receive greater priority and attention when the costs of conflict experienced by the industry were better understood?

Related

Ezra Levant: The more menacing method in which politicians control journalistsKevin Libin: Don’t dismiss Coderre’s Alberta bashing; all anti-pipeline politics are local

International research authored by the Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School in 2014 implies that most extractive companies don’t currently identify, understand and aggregate the entire selection of social-licence costs into a single number that would catch the attention of senior management or boards.

The most frequent costs result from lost productivity due to temporary shutdowns or delays, based on the research. For example, a significant, world-class mining project with capital expenditure of US$3 to $5 billion will suffer approximately US$20 million per week of delayed production in Net Present Value (NPV) terms, largely due to lost sales.

The timeframe for brand new projects to come on-stream nearly doubled in the last decade

The greatest costs of conflict were “the opportunity costs with regards to the lost value associated with future projects, expansion plans, or sales that didn’t go ahead.” Probably the most overlooked indirect costs were those “resulting from staff time being diverted to managing conflict – particularly senior management time, including in some cases that of the CEO.”

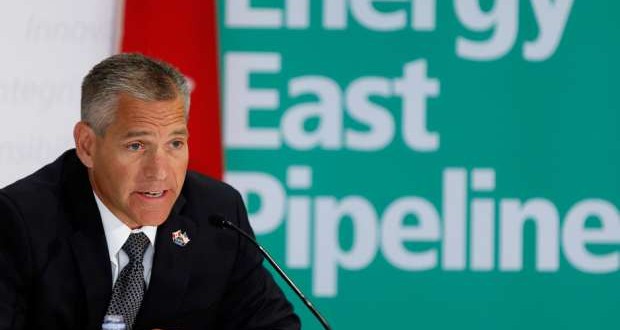

The apparent flaws that have severely damaged TransCanada’s interactions with Quebec local communities and politicians suggest that the energy industry still has a long way to go to fully recognize the functional managerial, operational and reputational costs of a social licence.

Undeniably, these costs are certain to increase. A 2010 are accountable to the UN Human Rights Council, citing a Goldman Sachs study of 190 projects operated by the major international oil companies, suggested that the timeframe for new projects to come on-stream nearly doubled in the last decade.

While the company costs for social licences could keep rising, their political costs might soon prove to be very expensive, too.

Social licences go hand in hand with people’s right to freely organize their communities according to the convictions. In lots of ways, this right represents a considerable civilizational advancement.

However, there’s a darker side towards the story book of stakeholder self-regulation and state disengagement. Social licences come also with political fragmentation that happens when people see themselves disconnected more and more using their fellow citizens in common projects and allegiances. No surprise people and locally based organizations infused with a social-licence doctrine have difficulties reconciling their interests using the common good of the Canadian society.

This lack of identification is not just fuelled by sovereigntist attitudes. Additionally, it reflects a far more deeply fragmented thought process, in which activists as well as political representatives increasingly begin to see the Canadian state in purely instrumental terms. It fosters disunity, since the absence of effective common action in the federal level only serves to throw communities back on themselves.

The energy sector and also the Canadian federation are generally immensely valuable but fragile resources. Underestimating the business and political costs of social licences might weaken Canada economically and politically, using the cost of repair weighing heavily around the next generation.

Bertrand Malsch is associate professor and Distinguished Research Fellow in Accounting, Smith School of Business, Queen’s University.

Finance News Follow us to find the latest Finance news

Finance News Follow us to find the latest Finance news